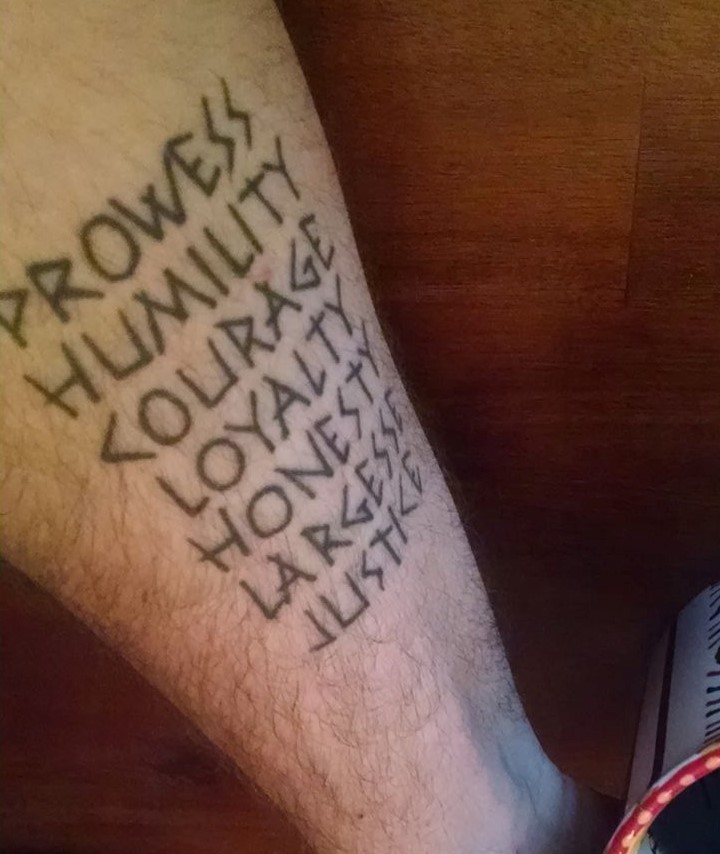

No, mom, that isn’t my arm.

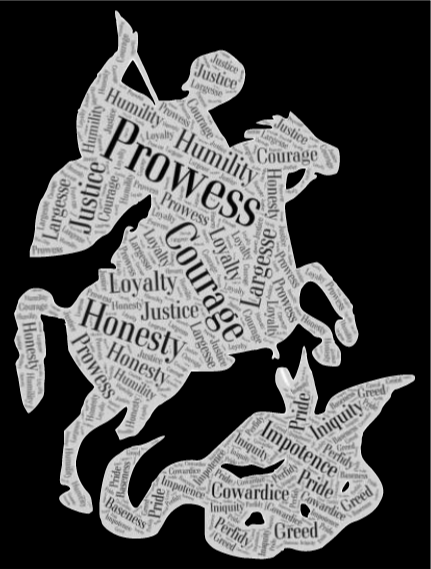

But those are the values I’m discussing; the virtues I’m seeking to develop. This is what I’m looking for in these volumes.

But words are tricky. We’re all pretty sure what they mean to us. But what they mean to someone else can be a mystery. And when you saddle words with value judgments, it becomes even more difficult. A word that references a heroic trait to one person might label a vicious monster to another. So here I’ll start trying to constrain these particular words.

I’m not going to define them, exactly. In the effort to be studious and not pretend to mastery, I’m going to label them and try to capture their conceptual flavor. One day, I hope to embody them, so that they need no definition, only an example. But that day, if it ever comes, is a long way from now.

Prowess – Prowess is the hardest to define in modern terms because it is intrinsically linked to violence and the capacity for violence. For good reasons, we tend to look askance at the idea of great capacity to be effective with violence as a “virtue.” But for Chivalry, it is essential to embody and project the fact that one is “a killer on each and every field they stand on.” (These words from from my knight, Count Alric KSCA, in his long definition of Prowess.)

But Prowess is not simply the ability to deal out violence. It encompasses the ability to truly transform the battle, whether in tournament or warfare, into a showcase of the martial arts. Winning in a mad scramble is not a demonstration of Prowess. True Prowess creates a bubble in which people can witness the reality of a person who can truly be a shield of the weak and a sword of justice.

Courage – This was defined by Aristotle as the virtue essential to all others. Courage is the will to bear the risks of demonstrating the other virtues. Prowess demands risking the body, the other virtues may risk fortune, face, friendship, or family. Courage supplies the steel to sustain a person through these risks.

Honesty – “Telling the truth can be dangerous business,” but Chivalry demands one chance that danger. But Honesty in this sense is more than relating facts accurately. It involves giving a true account of oneself in many ways. Honesty with oneself is essential to determine where one is falling short of being truly virtuous. And presenting a true face to others is the first step in dealing fairly with them, which is a foundation of Justice. To live a life without the protections of the various veils and shadows we use to prevent people from knowing us; to be the same person privately as publicly – this is radical Honesty.

Humility – This is also a difficult virtue, because it is so easily cheapened. Humility is the “check” on all other virtues. In the writing of Thomas Aquinas, the debasement and sacrifice of Christ was the ultimate expression of Humility. This is because humility is a recognition of who one truly is; lacking hubris or “airs” about one’s excellence and one’s place in the world. A person must not falsely claim to be less than they are any more than they should claim to be more. The truly humble person has their own internal voice to remind them, “you are but a human being” whether in victory or defeat.

Justice – I must confess that I remain very stuck on the idea of Justice as being each person getting their due. But I am not sure I will find that reflected in my sources. On some level, Justice is exemplified when people with power use that power to “set things right.” Sometimes, that is tearing down a barrier. Other times, it might be building a platform. It requires a keen and frank study of situations, permeated with Honesty to confront one’s own biases and assumptions, and the ability to see a situation from multiple sides. Justice also relies on the support of Courage to stand up to power, Humility to recognize one’s own role in wrong, and sometimes the Prowess to effect change.

Largesse – At the simplest level, Largesse is generosity. It is the recognition that Chivalry is a concept steeped in privilege and status. A little bit “to whom much is given, much is expected” and a little bit “with great power comes great responsibility,” Largesse tempers the tendency of Prowess to accumulate resources. Great Prowess comes with the power to amass power and wealth and status. Largesse requires that the person who seeks to be knightly to distribute those resources freely. That distribution might be on account of Justice (like when it is based on need) or because of Loyalty (when it is to honor someone else). Largesse also partners with Humility. With the true-seeing eye of Humility, one can see that they have more than they need and can share freely and without jealousy, envy, or undue restraint.

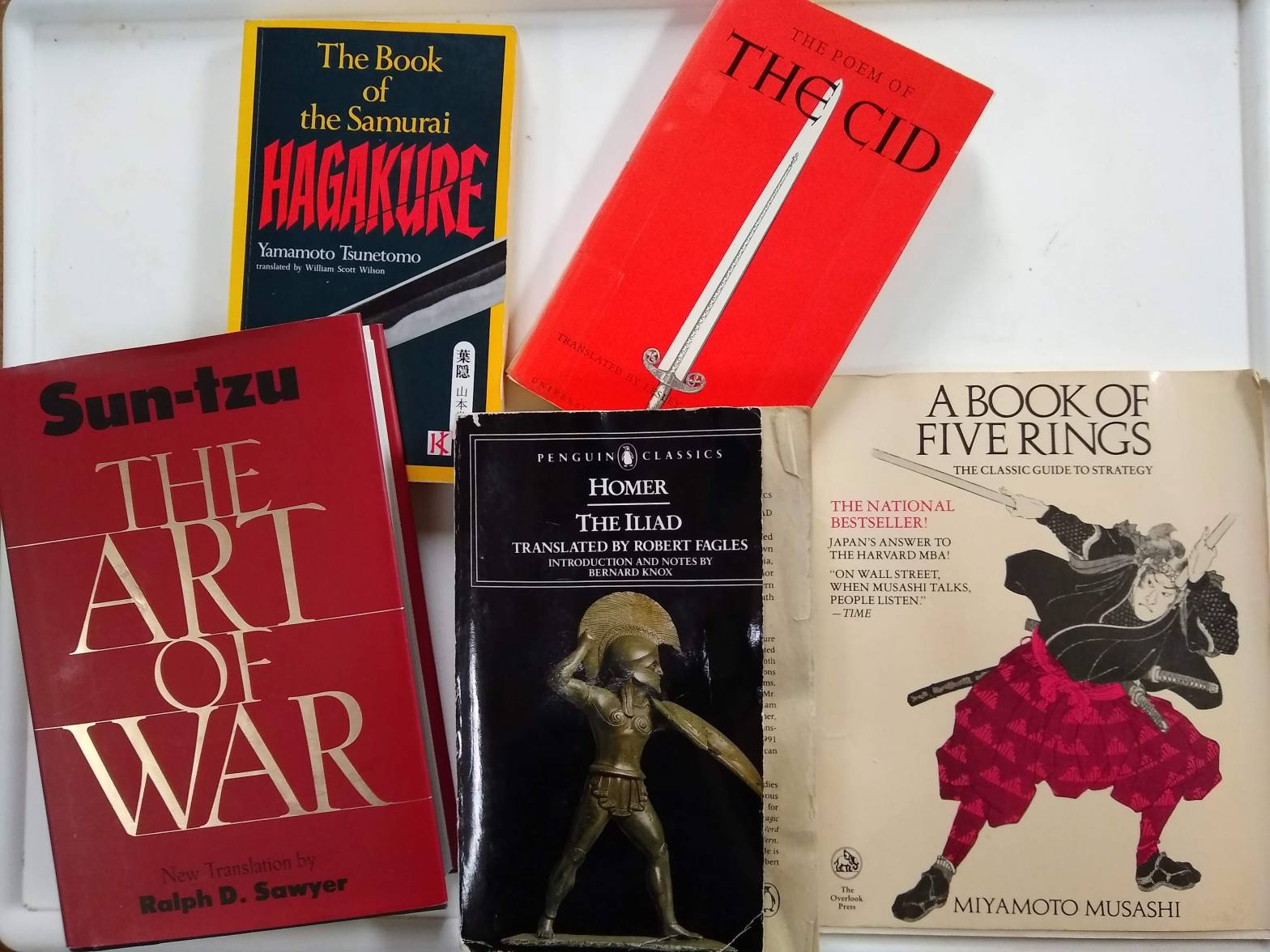

Loyalty – I think most of us go through life with a vague sense that Loyalty is a “I’ll know it when I see it” concept. Thankfully, two of my first sources deal extensively with loyalty, The Cid and Hagakure. In both, Loyalty clearly exists as a duty despite difficulty or lack or reciprocation. That duty is to another (or an organization, ideal, etc.), but it is not reliant on the one to whom it is due. Instead, the quality of Loyalty defines the “servant” as worthy. And it persists through trial and hardship. In this way, Loyalty seems to be intimately related to Humility, Courage, and Justice.

As I said, this isn’t a glossary. It isn’t the end. This is the beginning of a very long journey.