I’ve been meaning to read the story of Sundiata since I learned about him in a college Intro to African History class. So, when I started this project, I resolved to include this epic figure. I was not sure what to expect, other than a conquering hero and founder of empire. But I found the tale of a wise law-giver, mighty in both war and magic, honorable and fair-dealing in deed.

From the beginning, it was clear that the griots (the traditional historians and storytellers of the Mandinka) and I understood one another. Their purpose was promptly revealed as one close to my heart:

I teach kings the history of their ancestor so that the lives of the ancients might serve them as an example, for the world is old, but the future springs from the past

Sundiata, An Epic of Old Mali, Djibriltamsir Niane (G.D. Pickett, trans) (Pearson 2009), 3

Like many great stories, Sundiata’s tale began with a prophecy delivered by a travelling stranger. This hunter told a wise and kind king, Maghan Kon Fatta, of a hideous and magical Buffalo Woman he had encountered in his travels. If Maghan would follow his instructions and subdue the Buffalo Woman to make her his new wife, he would be assured of her a mighty king as a son. But when the son came, he seemed to have little promise. Although he was strong in the arms, the three year old boy rarely spoke and got around by crawling. He seemed interested in little but food. King Maghan continued to have faith the prophecy, but upon his death, palace intrigues left another wife, Sassouma, in control of a regency counsel with the aim to deny Sundiata his birthright.

By the time Sundiata reached seven years old, all seemed lost to his mother Sogalon. She was essentially exiled from the palace with her children. Her only solace was a small garden. But when she finally lashed out in frustration against Sundiata that he only sat and ate while Sassouma’s child brought her choice leaves from the forest, Sundiata rose and walked into the forest to bring her back an entire mature tree. From that point, Sundiata began to live and strong and active life on the path of the hunter. He assembled a band of other young hunters from neighboring territories with his skill and prowess.

No longer able to use his infirmity against him, Sassouma turns to witchcraft to eliminate Sundiata. But Mandinka curses rely on attaching to an evil quality in the target, so the witches attempt to goad Sundiata into anger by stealing from his mother’s precious garden. Perceptive hunter that he is, Sundiata catches them in the act:

‘Stop, stop, poor old women,’ said Sundiata, ‘what is the matter with you to run away like this? This garden belongs to all.’

Straight away his companions and he filled the gourds of the old hags with leave, aubergines, and onions.

‘Each time you run short of condiments come to stock up here without

Sundiata, 25.

This is just the first of Sundiata’s generosity. At every turn throughout his rise, Sundiata shares the bounty of his prowess with others. Even after the witches tell Sundiata they were hired to kill him with their magic, he offers them an entire elephant he and his companions killed so that they will not suffer from foregoing the cattle Sassouma offered them for payment. At other times, he shares the bounty of later hunts, the spoils of battle, and the comforts of hospitality with strangers from all lands. Even more, he recalls the little desires of people he meets and he greets even the most humble by name and recalls their family, leading one watcher to remark, ” There’s one that will make a great king. He forgets nobody.” Id., 34.

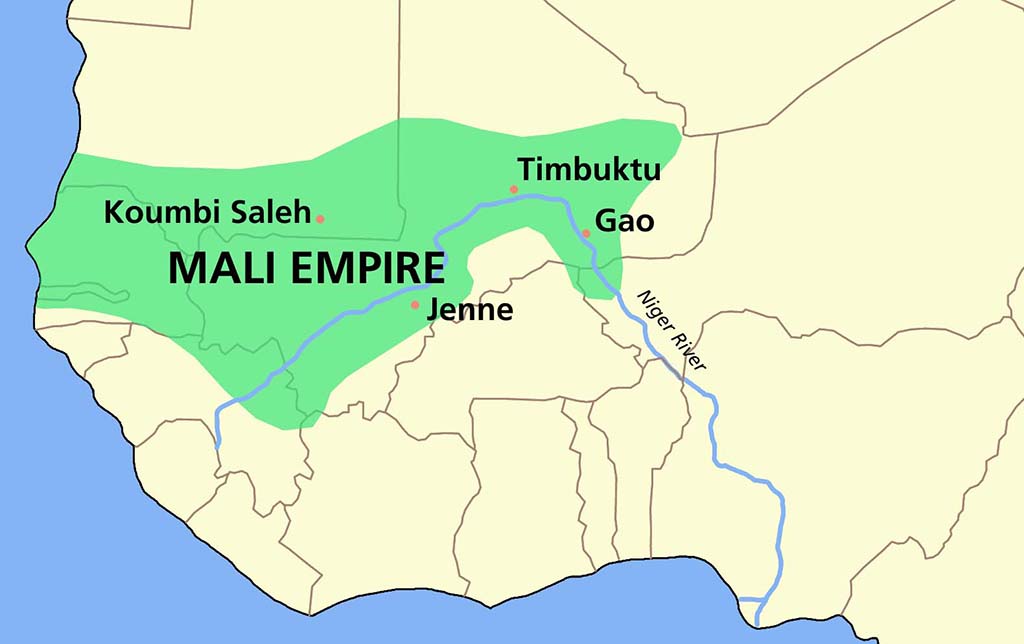

When Sassouma’s favored son becomes king, Sogalon takes her family into exile in the kingdom of Ghana. It is there that Sundiata grows into an adult and takes up the ways of a warrior. In his first battle, the future king’s courage is evident:

[Sundiata] hurled himself on the enemy with such vehemence tht the king feared for his life, but Mansa Tounkara admired bravery too much to stop the son of Sogolon.

Id., 36-37.

Eventually, the son of the Buffalo Woman learns that an evil wizard has taken power in his ancestral lands and is terrorizing the surrounding kingdoms, conquering lands all around. He assembles a force from the companions he has made and their countrymen to fight back against this wizard who wears the skin of men. But even in this quest to fulfill his destiny and take the throne, Sundiata is not motivated only by a search for glory and lordship. He also seeks to restore the countries of people disposed by the wizard:

‘I defend the weak, I defend the innocent, Fakoli. You have suffered an injustice so I will render you justice.’

Id., 61

I was thrilled by Sundiata’s story, as thrilled by it as I was disappointed by Digenis Akrites‘. Here was a hero who rose from unpromising origins—an apparently failed prophecy. He was sent into exile unjustly, earned a place in a foreign land though kindness, wit, and courage. And then returned, aided by loyal friends and commanding an army with skill, on a quest to protect the weak, restore justice, overcome evil, and take his destined place as king. This was knighthood as I could recognize it.

The griots who tell the story of Sundiata do not claim to tell the entire story or the entire truth. In fact, in several places, they claim outright that there are secrets known to the griots that should not be revealed to other people. But I did find the story true to the promise Maghan Kon Fatta made to his son when he presented him with a griot to be a companion:

‘From his mouth you will hear the history of your ancestors, you will learn the art of governing Mali according to the principles which our ancestors have bequeathed to us.’

Id., 17.

I’ll get into the principles Mansa Sundiate Keite established in another post. His reign left humanity with the great gift of a comprehesive constitution; one recognized as one of the world’s first charters of human rights.

But this is why I study these stories, in spite of the flaws and sins of all of our collective ancestors. Their acts were often hideous, their words could be the worst lies. But their principles—the high-minded and lofty things they assured us motivated their actions—those may yet bear us fruit.